The CCC Under Surveillance: The Civilian Conservation Corps and the Military Intelligence Division

In 1935, the Theatre of Action, a New York-based radical theatre group, staged a production of the play The Young Go First at the Park Theatre in New York City. Peter Martin, George Scutter, and Charles Friedman wrote the play; it was directed by Alfred Saxe and Elia Kazan, who would later make a career in Hollywood but would testify against suspected Communists in Hollywood at the McCarthy hearings. The plot revolved around what the authors claimed were George Scutter’s real experiences at a Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) camp. The play portrayed the camps as a militaristic environment and depicted a group of boys who revolted against the system.

The Theatre of Action was a radical worker’s theatre group first known as the Workers Laboratory Theatre, but which changed its name in 1935. During this change, they also adjusted the style of plays they made, becoming known for their “agitprop” theatre (a combination of the words agitation and propaganda). Their short plays often included mass chants and calls to revolutionary action, and were meant to influence the audience. The Young Go First, though longer, still relied on agitprop style elements. Although they would not call themselves subversive, they certainly were attempting to create social awareness through their plays.

These appeals to social activism brought the Theatre of Action under surveillance by the Military Intelligence Division (MID), which suspected the group of harboring Communist sympathies. The RIAS is in possession of the MID’s surveillance reports between 1917 and 1941; these files are available on microfilm in the U.S. Military Intelligence Reports: Surveillance of Radicals in the United States, 1917-1941 collection, and contain the reports on the CCC camps.

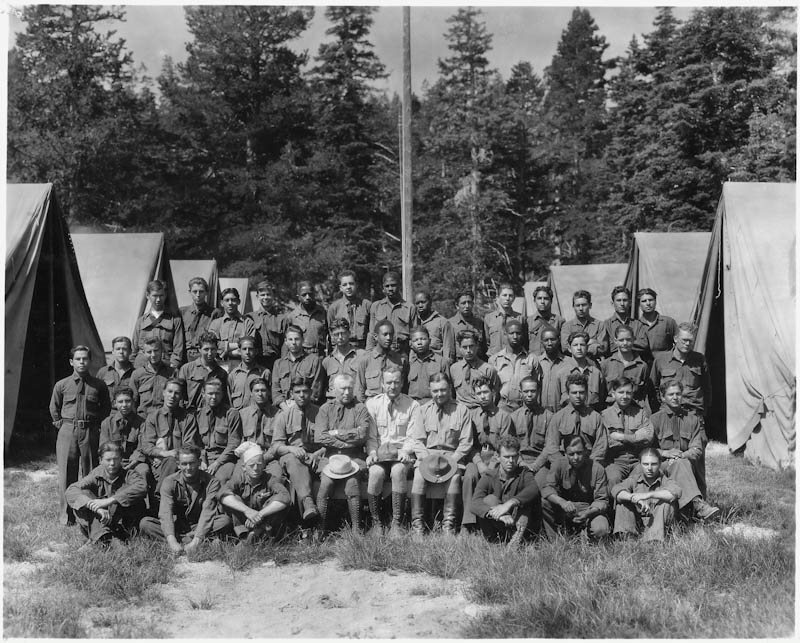

The play takes place in a Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) camp. The CCC was a New Deal program, founded in the midst of the Great Depression in 1933, that recruited unemployed young men to work on projects to conserve and develop America’s natural resources. These boys and men would plant trees, take care of wildlife by building shelters and refugees, and they would fight forest fires, among other conservation efforts. The people employed by the CCC would all live together in camps. Even though the CCC provided relief for the unemployed, the supervision of the program by the US Army prompted criticism. Its detractors on the Left, in particular, suspected that the CCC, with its camps, drill, and militaristic organization, was secretly preparing young men for war. In turn, the army’s Military Intelligence Division monitored criticism of the camps.

The Young Go First squarely took aim at the camps; according to a report by the MID the play: “urges all young men going to CCC camps to disregard discipline; to rebel against their superiors; to refuse to do any labor assigned that does not meet with their approval, and to organize radical cells in all camps for purpose of sabotage” An advert for the play in the Marxist magazine New Masses reflected the core ideas of the playwrights about the camps: “A Drama of the CCC Camps. Where hundreds of thousands of America’s youth are being mobilized and militarized for the impending war.” Such calls to action brought the play to the attention of the MID

The MID was monitoring not only the Theatre of Action and their “subversive” play, but, as the collection at the RIAS shows, they investigated rumors of Communist or subversive behavior throughout the CCC system, including reports they received from CCC camp leadership. This subversive behavior could be anything from the distribution of Communist pamphlets to attempts to recruit their fellow campmates to Leftist organizations. These tensions reflected the class dynamics of the CCC. Historians have argued that the Conservation Corps did, indeed, seek to cultivate certain attitudes among its participants. Camp organizers believed that through an outdoor environment, disciplined physical labor, and communal activities could help turn young, unemployed and potentially disaffected young men into respectable middle-class citizens – something many Communists and many other Leftists objected to.

The MID also investigated other incidents involving the dissemination of materials on the campgrounds. In December 1933, a report signaled that camps in New York and Connecticut had found circulars distributed by the Young Communist League. Addressed to the “Men of the CCC”, the pamphlets called on camp inhabitants to rebel against military discipline and demanded the “removal of all military officers,” an end to segregation and “Jim-Crowing”, and a guarantee that CCC labor would not be used to break strikes. Finally, it called on CCC participants to fight “Against imperialist war and for the defense of the Soviet Union.” The pamphlet shows that the League felt that the CCC camps were preparing young men for war and that the next war would not be in the interest of the people but for the benefit of Wall Street. To stop this from happening, the men in the in the camps should unionize and fight back against military control. A year later, camp leadership reported that they had found a copy of the “Camp Spark,” a paper that was “evidently sponsored” by the Young Communist League in a camp in Vermont.

The play The Young Go First received a mediocre review from the critic writing for the New York Times, who felt the play was “too quiet an evening; it is a cracker-box discussion where a brawl would be indicated.” The reviewer the review had expected more of the play and did hope that the Theatre of Action could do better in the future. Perhaps this was true, but they did get the attention of the MID and challenged the CCC leadership while shining a light on what happened in the camps.

This piece was written using the following newspapers and magazines:

– New Masses, May 21, 1935.

– The CCC New York Times.

The following reports:

– MID Theatre of Action Report.

– U.S. Military Intelligence Reports: Surveillance of Radicals in the United States, 1917-1941.

And the following academic journal articles:

– Anne Fletcher, Rediscovering Mordecai Gorelik: Scene Design and the American Theatre, (Carbondale, Southern Illinois University Press: 2009)

– Howard L. Lange, The CCC. A Humanitarian Endeavor during the Great Depression. (New York: Vantage

Press, 1984).

– Eric Gorham, “The Ambiguous Practices of the Civillian Conservation Corps.” Social History 17, no. 2 (1992):229-49.

CCC Subversive Incidents.