Clinton, Yeltsin, and the Hope for a New Partnership

For nearly half a century, the United States and the Soviet Union were locked in a global rivalry that defined international politics and shaped the post-World War II world. However, when the Soviet Union dissolved in 1991 and the Russian Federation took its place, the Cold War came to an abrupt end. Russian President Boris Yeltsin and newly inaugurated U.S. President Bill Clinton saw this as an opportunity for change in U.S.-Russian relations. Their personal relationship, as documented in official memoranda, reflects both the hope for a fresh partnership and the tensions that would soon resurface.

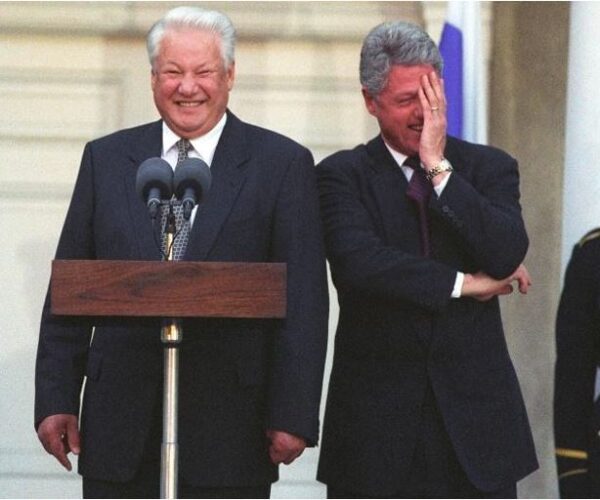

After Clinton took office in January 1993, his relationship with Yeltsin got off to a promising start. The two presidents called each other by their first names, and in their first phone call, Clinton assured Yeltsin that “Russia [would] be a top priority for U.S. foreign policy during my Administration,” and expressed his determination to build “the closest possible U.S.-Russia partnership.” Yeltsin, in turn, called the meeting “very good” and said he was confident their relationship would only grow stronger.[1] Over Clinton’s first year, two summits helped solidify the U.S.–Russian strategic partnership, leading to close cooperation on a range of issues, from market reform and military conversion to nonproliferation and space exploration. The clearest symbol of their friendly relationship was a joint press conference in New York in 1995 when Clinton and Yeltsin shared a hearty, unscripted laugh that made headlines around the world.

Behind the warm words and early cooperation, both leaders carried distinct hopes for the post–Cold War world. After the collapse of the Soviet Union and, with it, much of Russia’s pride, Yeltsin was eager to see the establishment of a new international system in which Russia would be treated as a true partner of the West. Clinton, in turn, viewed Russia’s transformation as key to building a more stable and secure international order and saw in Yeltsin the best opportunity to help build a stable, democratic, market-oriented Russia: “whatever we can to help Russia’s democratic reform to succeed.” In those early years, both leaders envisioned a new kind of relationship between the United States and Russia—one built on cooperation rather than rivalry.

Despite the outward warmth between the two leaders, underlying tensions soon began to emerge, especially around the question of NATO’s future. Russian leaders believed that, in the wake of the Cold War, they had received assurances that the alliance would not move eastward. Yeltsin expressed his strong stance against NATO expansion in a letter to Clinton in September 1993, stating that “security must be indivisible and must be based on [a] pan-European security structure,” meaning a system in which European security would be shared by all, rather than dominated by one alliance.[2] In response, Clinton’s team offered reassurances: Secretary of State Warren Christopher proposed the Partnership for Peace as a framework that would treat all former Soviet and Warsaw Pact countries equally, a proposal Yeltsin praised at the time as “a stroke of genius.” But while Russia was promised cooperation, the U.S. increasingly backed enlargement. By early 1994, Clinton was telling Central European leaders that expansion was inevitable, with countries like Poland, Hungary, and the Czech Republic expected to join. Yeltsin felt betrayed, later referring to it as “a betrayal of the Russian people.”

The 1999 NATO bombing of Belgrade marked one of the most fraught moments in U.S.–Russian relations during the Clinton–Yeltsin years. Russia, a historic ally of Serbia, had not been consulted about the campaign, and the strikes came just weeks after Poland, Hungary, and the Czech Republic formally joined NATO, deepening the sense in Moscow that Russia was being sidelined. In a telephone call between the two presidents, Yeltsin condemned the bombing as “a giant humanitarian catastrophe” that had done “significant damage” to U.S.-Russian relations. Yet, even as the political tensions between the countries grew, the conversation ended on a warm note, with both presidents expressing a desire to continue cooperating. Clinton stated that he felt “good about this conversation, Boris,” and Yeltsin agreed with him.

In the end, the relationship between Clinton and Yeltsin embodied both the promise and the limits of post–Cold War cooperation. Their personal warmth and shared optimism briefly opened the door to a new kind of partnership between the United States and Russia that was based on mutual respect, democratic reform, and strategic collaboration. But as geopolitical realities reasserted themselves, over NATO primarily, their vision of a stable, united Euro-Atlantic space gave way to renewed tensions. Still, the Clinton–Yeltsin years remain a unique moment in U.S.–Russian relations, when personal ties, shared optimism, and frequent calls gave real hope for a different kind of partnership.

Digital resources at the RIAS:

- The Digital National Security Archive, databases:

- U.S.-Russia Relations: From the Fall of the Soviet Union to the Rise of Putin, 1991-2000

- Soviet-U.S. Relations: The End of the Cold War, 1985-1991

Additional sources consulted:

- Talbott, Strobe, The Russia Hand: A Memoir of Presidential Diplomacy. Random House, 2002.

- “NATO Enlargement in 1994 (NSC): What Actually Happened,” CFR Education, https://education.cfr.org/learn/simulation/nato-enlargement-1994-nsc/what-actually-happened

Secondary literature:

- Shevtsova, Lilia. Yeltsin’s Russia: Myths and Reality. Brookings Institution Press, 1999.

Photographs:

- Wikimedia Commons, President Bill Clinton greets President Boris Yeltsin of Russia.jpg, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:President_Bill_Clinton_greets_President_Boris_Yeltsin_of_Russia.jpg

- Wikimedia Commons, Boris Yeltsin and BillClinton 1999-11-18.jpg, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:BorisYeltsin_and_BillClinton_1999-11-18.jpg

- Wikimedia Commons, President Bill Clinton and President Boris Yeltsin of Russia during the Hyde Park meeting press conference (02).jpg, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:President_Bill_Clinton_and_President_Boris_Yeltsin_of_Russia_during_the_Hyde_Park_meeting_press_conference_(02).jpg