Generations of Resistance: How Current Student Social Movements Build Further on Protests of the 1960s and ‘70s

University campuses across the United States have once again become epicenters of protest since the events on October 7th, 2023, in response to the escalated violence in Gaza. Nationwide, students have mobilized to oppose both the Israeli military actions against Palestinians and the perceived complicity of their own universities and the U.S. government. These protests have sparked a wave of campus activism that reminds some of an earlier chapter in American history when student activists in the 1960s and ‘70s demonstrated against the Vietnam War. This comeback of student-led social movements raised the question of the extent to which current-day protests are rightfully associated with the demonstrations of more than fifty years ago.

Records from the anti-Vietnam War movement, including those from The New Mobilization Committee, Students for a Democratic Society (SDS), the Fifth Avenue Vietnam Peace Parade, and the National Peace Action Coalition (NPAC), show that, despite differences in structure and focus, students from the 1960s and ‘70s and those of today shared some common themes and approaches.

A defining characteristic of the anti-Vietnam War movement was its claim that it represented a moral and popular majority. The New Mobilization Committee described itself as a “majority movement” and emphasized its wide coalition of support, ranging from students and labor unions to religious groups and veterans. NPAC similarly portrayed itself as speaking for the broader American public. These organizations framed opposition to the war not only as the moral high ground but also as a pragmatic economic stance, suggesting that ending the war would relieve financial pressure on working-class communities

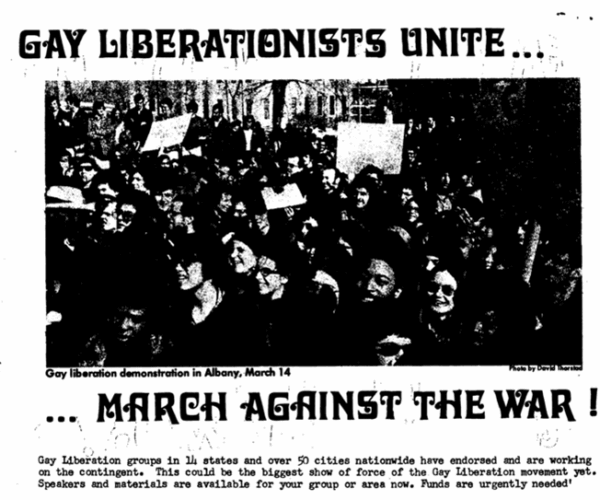

At the same time, student-led groups expanded the conversation by connecting the Vietnam War to systemic inequalities within the United States. New Mobilization Committee materials gave attention to racial injustice, stating that solidarity with “black and brown people” was part of their goal.[2] Besides that, specific identities were motivated to join the movement. Pamphlets circulated with slogans like “Gays Against the Vietnam War” and “Women Unite Against the War.In doing so, they made the anti-war movement a broader topic and emphasized the interconnectedness of different struggles under a shared striving for resistance.

Today’s student protests over Gaza suggest a similar approach. The movement is not an isolated cause but falls within the broader landscape of social justice activism. While criticism of Israeli military actions has been present on campuses for years, the scale and urgency of demonstrations have grown significantly since the events of October 2023. National Students for Justice in Palestine (National SJP) has emerged as a key organizing force, much like the national anti-war coalitions of the ’60s and ’70s. It coordinates both on-the-ground protests and digital campaigns, providing most information and organization about the growing movement.

Like their anti-war predecessors, these activists do not see the Gaza conflict as a single issue. National SJP explicitly connects Palestinian liberation to other justice movements. For example, they refer to the U.S. as “Turtle Island” as a sign of solidarity with Indigenous peoples and their histories of resistance. Their messaging connects Palestinian freedom to movements for racial equity, climate justice, LGBTQ+ rights, and decolonization. As they state, “all pursuits for freedom, justice, and equality are materially intertwined,” showing a vision that challenges state violence, capitalism, colonialism, and imperialism at the same time.

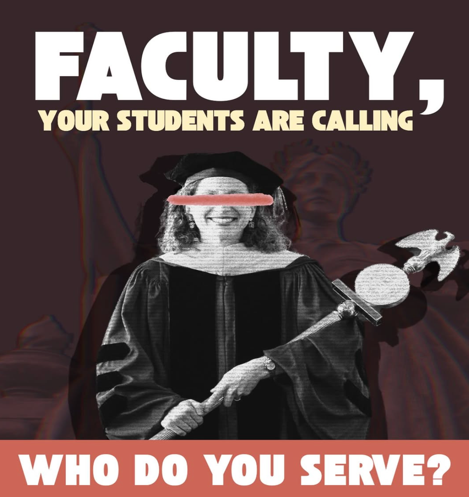

Despite these similarities, there are also key differences between the Vietnam-era protests and today’s Gaza-focused activism, for example in their targets. Anti-Vietnam War protests primarily aimed their demands at the federal government, in particular the Nixon administration. Even though there are instances of student protests criticizing their own university, most national student movements sought to shift U.S. foreign policy and end the war mainly through pressure on the national government. This is seen in their communications through pamphlets and protests signs that state “End the War Now” or “Bring Home the Troops”. Student activists in these days too criticize their national government and its behavior towards the conflict in Palestine. The position of the U.S. federal government became a hot topic during the presidential elections of 2024, with many young Americans choosing not to support Kamala Harris based on her stance towards Israel. However, many of today’s student protests concentrate their energy on university policies, which is a dominant narrative during student protests. Activists demand institutional divestment from companies linked to the Israeli military, transparency in

financial holdings, and academic boycotts. Though frustration with U.S. foreign policy remains visible, there is a stronger emphasis today on holding universities directly accountable. A key difference between the war in Vietnam and the violence in Gaza is that the U.S. government was a direct participant in the former. In contrast, today the government and academic institutions are being criticized for not doing enough to stop the latter. Therefore, activism and criticism on U.S. accountability and complicity in the two violent eras differ in their message.

Still, the underlying strategies of resistance remain consistent. Then and now, university campuses serve as vital places for political organization. Student associations play a key role in coordinating action, building coalitions with faculty and local communities, and organizing events like teach-ins, sit-ins, and walkouts. The tools may have evolved from paper pamphlets to digital media, but the spirit of dissent continues. Protesters today proudly place themselves in the tradition of student movements in the past, highlighting their legacy to legitimize and inspire their own efforts. Times have changed, but student resistance builds further on the

Digital resources available at the RIAS

- ProQuest History Vault: Anti-Vietnam War demonstrations in Washington, D.C. and San Francisco, April 24-25, 1971

- ProQuest History Vault: April 17, 1965, March on Washington anti-Vietnam War demonstration.

- ProQuest History Vault: Fifth Avenue Peace Parade Committee Flyers.

- ProQuest History Vault: Fifth Avenue Vietnam Peace Parade Committee demonstrations with affidavits of police violence.

- ProQuest History Vault: National Convention of the U.S. Antiwar Movement, December 4-6 1970, from National Peace Action Coalition Records.

- ProQuest History Vault: press releases, fact sheets, and pamphlets of the New Mobilization to End the War in Vietnam.

- ProQuest History Vault: SDS anti-Vietnam war activity, March on Washington, posters, memos and press release.

- ProQuest History Vault: SDS Bulletin

- ProQuest History Vault: Students for a Democratic Society, Port Huron Statement.

Additional sources

- Josh Freeman, ‘’There was nothing to do but take action’: The encampments protesting for Palestine and the response to them’, Higher Education Policy Institute, (2025).

- Moustafa Bayoumi, ‘Not changing course on Gaza was a colossal mistake by Kamala Harris’, (11 November 2024) https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2024/nov/11/election-harris-gaza-policy (version 28 May 2025).

- National SJP, ‘Who are we?’ https://www.nationalsjp.org/about (version 28 May 2025).

- Sam Cabral and Ana Faguy, ‘What do pro-Palestine student protesters at US universities want?’ (3 May 2024) https://www.bbc.com/news/world-us-canada-68908885 (version 28 May 2025)

- ProQuest History Vault: Anti-Vietnam War demonstrations in Washington, D.C. and San

Francisco, April 24-25, 1971. Link: https://www.proquest.com/hvhistoryvault/docview/3053560914?rd=HV&sourcetype=Archival%20Materials - Students for a Democratic Society at UIC, @sdsatuic, ‘Join UIC (and the dozens of other campuses across the country) for a rally and march for the @nationalsjp day of action’, 12 September 2024. Link: https://www.instagram.com/p/C_0lm3gxw-M/

- National SJP, @nationalsjp, ‘FACULTY: WHO DO YOU SERVE?’, 9 May 2025.

Link: https://www.instagram.com/p/DJaTz0-NdAi/