White Noise: William Luther Pierce and the Propaganda Engine of Racial Extremism

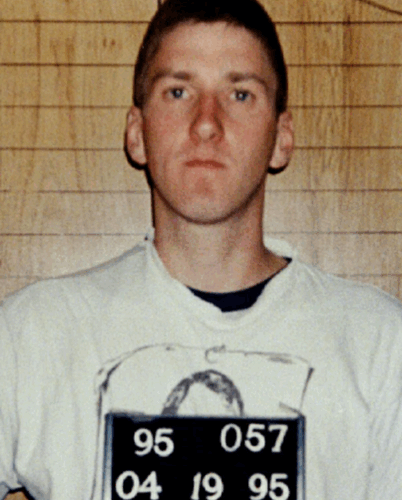

On the morning of April 19th, 1995, a rental truck was parked outside the Alfred P. Murrah Federal Building in downtown Oklahoma City. At 9:02, the truck detonated, blowing a crater in the side of the Murrah building, killing 168 people and injuring another 648. The explosion turned downtown Oklahoma City into a war zone.

Timothy McVeigh, a 26-year-old Gulf War veteran and the attack’s perpetrator, was picked up accidentally during a routine traffic stop. Two days later, he was nearly released from police custody. Only when tracing the registration numbers found on the wreckage of the truck did the authorities realize they already had the Bomber in custody. In the months that followed, McVeigh was subjected to extensive interrogation. McVeigh described deep feelings of isolation and resentment, citing events like the 1993 Waco Standoff as evidence that the federal government was acting against its citizens. At the roots of his radicalization were books and pamphlets distributed by American neo-Nazi groups—anti-government texts that spun crisis narratives of racialized decline and the tyranny of the federal government, circulated through gun shows and early conservative and ultraright-wing sites like Don Black’s Stormfront.com, founded in 1992.

The novels McVeigh had read fell into a long lineage of radical narratives disseminated through literary media and emerging technologies, circulating intolerant and often violent ideologies, recruiting, and entertaining. When the internet revolutionized communication in the 1980s, far-right thinkers like David Duke and Don Black were quick to establish websites for National Socialists to meet and interact—archaic precursors to the 4chans of today. One of the most influential personalities in the far-right ecosystem in the second half of the twentieth century was William Luther Pierce (1933–2002). Pierce, the son of a Texas insurance agent, would transform his rising career as a physicist in academia—he gained tenure at 33—into a career as the intellectual vanguard of the post-war far right. After he radicalized in the ’60s, in no small part due to the New Left wave of the civil rights movement, Pierce grew involved with George Lincoln Rockwell’s American Nazi Party. After Rockwell’s assassination in 1967, Pierce left and began the National Youth Alliance in 1968. Starting from what once was the Youth for Wallace group, the youth faction of the Southern Democrats under George Wallace. Pierce would take over the group’s mailing list and start editing its periodical Attack! Later rebranded to National Vanguard

Pierce’s Propaganda Machine

Through his newsletter, Pierce constructed an alternative reality based on foundational myths of Zionist occupational governments and the supremacy of the white race. National Vanguard/Attack! is full of anti-government conspiracies, blaming the Jews for the failings of the American state, and calling against the involvement of America in the Middle East. Strikingly, the magazine included a weekly column called “Revolutionary Notes,” where patriots are instructed on how to build bombs, which firearms are best for urban defense, and survival techniques. Despite clearly inciting violence, the magazine framed itself as just presenting information and “assumes no responsibility for any damage caused by its readership,” whatever that could potentially be.

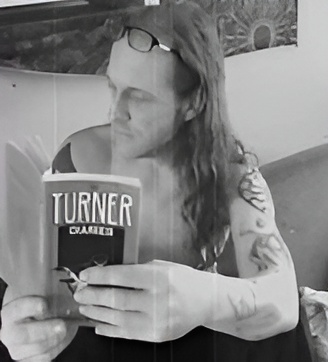

Yet Pierce would take the column a step further; in 1975, he created a fictitious serial in the magazine meant to indoctrinate and instruct. This series, later known by its book-length title The Turner Diaries, is an apocalyptic tale of a world where whites are marginalized and exterminated by a tyrannical government known only as “the system.” The Turner Diaries—essentially a fictionalized extension of Revolutionary Notes—would become the foundational text of the militia and skinhead movements.

Pierce, building on the narrative frameworks of The Turner Diaries, next penned Hunter in 1989. The story of Oscar Yeager, a government contractor and Vietnam vet who gleefully spends his free time hunting down and shooting interracial couples. In his 2001 biography, The Fame of a Dead Man’s Deeds: An Up-Close Portrait of White Nationalist William Pierce, Pierce claimed he related to Yeager on a personal level, saying he was someone he’d like to be.

In 1999, Pierce bought Resistance Records, a white power label that had emerged from the skinhead punk scene of the 1980s and ’90s. It featured groups like RaHoWa (Racial Holy War), Aryan, and Angry Aryans—all white power punk bands known for their anger and racist lyrics. Resistance Records next moved into graphic art; in 1999, they published a comic strip titled New World Order Comix #1: The Saga of the White Will. It followed a 17-year-old boy, Will, who works tirelessly to segregate his high school from codified “Muggers” and “Drug Dealers.”

Pierce’s Propaganda Machine Hits Its Peak

The multimedia empire expanded into video games, with titles such as Ethnic Cleansing (2002) and White Law (2003)—poorly designed shooters developed and published by the National Alliance—that had players gun down armed Jews while playing as Klansmen to the soundtrack of Resistance Records songs. Meanwhile, Pierce travelled the globe, building ties with fascist groups in Europe like the Nationaldemokratische Partei Deutschlands (now banned due to terrorism) and the British National Party, creating a transnational network of fascists. By the time of his death from kidney failure in 2002, Pierce had transformed a magazine into a multimedia empire, presiding over two record labels, video games, a literary imprint, and a party with membership in 22 states across the US.

Yet the events inspired by his book would also be the undoing of the American Far Right in the 20th century. In the wake of the attack, the American government began fiercely cracking down on American militias, the southern poverty law center, an organization dedicated to the protection of civil rights and the tracking of extremism found that by the year 2000, there were only around 200 militia groups active in the US, a decrease from nearly 900 in 1996.

The internet became a staging post for smaller, decentralized cells operating out of basements and attics all across the country. Through McVeigh, Pierce arguably set the stage for the memetic mobilization that has unfolded throughout the last decade. Though, as the head of the largest white nationalist organization in the US Pierces publication was the biggest ,the archives show us there were dozens more like him. Hate-filled publications, like the antisemitic Christian Advocate and The Stormtrooper, published by the American Nazi Party and preserved on microfilm, document the persistent influence of figures like Pierce throughout recent history.

Archival materials available at the RIAS:

- Federal Bureau of Investigation. American Nazi Party – Monograph.S. Department of Justice, n.d. Accessed through the digital archive of the Roosevelt Institute for American Studies.

- Federal Bureau of Investigation. The Order.S. Department of Justice, n.d. Accessed through the digital archive of the Roosevelt Institute for American Studies.

- The Right Wing Collection of the University of Iowa Libraries, 1918–1977. Accessed through the digital archive of the Roosevelt Institute for American Studies

Secondary source material at the RIAS:

- Stock, Catherine McNicol. Rural Radicals: Righteous Rage in the American Grain. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1996. Accessed at the physical archive of the Roosevelt Institute for American Studies, Middelburg, The Netherlands

Other Works Consulted

Primary Material:

- Ethnic Cleansing, video game (Resistance Records, 2002), developed by the National Alliance.

- Griffin, Robert S. The Fame of a Dead Man’s Deeds: An Up-Close Portrait of White Nationalist William Pierce. 4th ed. Self Published, 2001.

- McDonald, Andrew (pseudonym of William Luther Pierce). Hunter Barricade Books, 1996. https://archive.org/details/hunter-by-andrew-macdonaldwilliam-luther-pierce-1989/mode/2up

- McDonald, Andrew (pseudonym of William Luther Pierce). The Turner Diaries. Barricade Books, 1996. https://cdn.preterhuman.net/texts/unsorted/TurnerDiaries.pdf

- Pierce, William L. The Saga Of… White Will! 1st ed. National Vanguard Books, 1993. https://archive.org/details/national_vanguard_1993_white_will

- White Law, video game (Resistance Records, 2003), developed by the National Alliance.

Secondary Material:

- Baele, Stephane J., Lewys Brace, and Travis G. Coan. “Variations on a Theme? Comparing 4chan, 8kun, and Other Chans’ Far-Right “/Pol” Boards.” Perspectives on Terrorism 15, no. 1 (2021).

- Berger, J.M. “The Turner Legacy: The Storied Origins and Enduring Impact of White Nationalism’s Deadly Bible.” Centre for Counter-Terrorism (2016). Accessed January 13, 2024. https://www.jstor.org/stable/resrep29403

- Cullick, Johnathan S. “The Literary Offenses of a Neo-Nazi: Narrative Voice in The Turner Diaries.” Studies in Popular Culture 24, no. 3 (2002): 87–99. Accessed January 13, 2025. https://www.jstor.org/stable/23414969

- Joyce, Stephen. “Conspiracy Narratives and American Apocalypticism in The Turner Diaries.” In Plots: Literary Form and Conspiracy Culture, 1st ed. Routledge, 2021. https://www.taylorfrancis.com/books/edit/10.4324/9781003048657/plots-literary-form-conspiracy-culture-ben-carver-dana-craciun-todor-hristov?refId=c296101f-61de-4798-99a2-0dad18b2fe30&context=ubx

- Lewis, Jon, and Haroro J. Ingram. “Founding Fathers of the Modern American Neo-Nazi Movement: The Impacts and Legacies of Louis Beam, William Luther Pierce, and James Mason.” National Counterterrorism Innovation, Technology, and Education Center (NCITE) 1, no. 1 (2023): 1–85. Accessed April 19, 2025. https://extremism.gwu.edu/sites/g/files/zaxdzs5746/files/2023-05/founding-fathers-final.pdf

- McAlear, Rob. “Hate, Narrative, and Propaganda in The Turner Diaries.” The Journal of American Culture 32, no. 3 (2009): 192–202. Accessed April 14, 2025. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/j.1542-734X.2009.00710.x

- Potok , M. (2013, March 4). The Year in Hate and Extremism. Splcenter.org. Retrieved June 20, 2025, from https://www.splcenter.org/resources/reports/year-hate-and-extremism/

Recommended Readings:

- Belew, Kathleen. Bring the War Home: The White Power Movement and Paramilitary America. 2nd ed. Harvard University Press, 2019.

- Kelly, Megan, Alex DiBranco, and Julia R. Decook. “Red Pill to Black Pill” in Misogynist Incels and Male Supremacism, New America, 2021.

- Lyons, Matthew N. Alt-Right: The White Power Roots of the Alt-Right. London: Pluto Press, 2017.

- Mulloy, Darren J. Years of Rage: White Supremacy in the United States from the Klan to the Alt-Right. 1st ed. Rowman & Littlefield, 2021.

Images:

- Unknown author. William Luther Pierce. Wikimedia Commons. Public domain. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:William_Luther_Pierce.jpg.

- United States Department of Justice. Timothy McVeigh Mugshot (3×4 Cropped). Public domain. Wikimedia Commons. Accessed June 20, 2025. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Timothy_McVeigh_Mugshot_(3x4_cropped).png.

- Hippie from Hell. October 24, 2016. Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International. Wikimedia Commons. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Rijndaal-_Hippie_from_Hell.jpg.

- Peters, Marek. Neonazi‑Skinheads – Weiß und stolz. Photograph, August 19, 2006. Wikimedia Commons. Licensed under GNU Free Documentation License 1.2. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Neonazi‑skinheads‑weiss‑und‑stolz.jpg.