How the Federal Government Created a New Generation of Writers

On May 10th, 2020, the LA Times published an article by David Kipen about the rising number of news reporters and other writers facing unemployment following the COVID-19 pandemic. In an attempt to create a future for them, Kipen decided to look to the past. After all, the United States has faced economic peril and uncertainty before, and government patronage of and public support for money to the arts has existed as long as artist has been a career path.

The Great Depression is a prime example of this. Responsible for singlehandedly changing the course of the 20th century, this economic crisis led to record unemployment numbers. In 1932, Franklin D. Roosevelt was elected on a platform of job creation, and by 1933 the New Deal’s Civil Works Administration was created to ensure employment for four million people – most of whom worked in construction projects.

But blue-collar workers weren’t the only ones without jobs. A 1933 survey from the Federal Emergency Relief Administration covering 180,000 families demonstrated that white-collar workers were largely sitting at home. So, what do you do when you have jobless white-collar workers desperate to make some money and support their families? Set up a large-scale project capable of creating jobs across the board.

In come Henry Alsberg, George Cronyn, and Katherine Kellock. By the time the survey came around, the idea of a Federal Writers’ Project had been floating around for a while in various forms, and Alsberg had the idea to create “a diverse collection of essays which could attract attention to the whole of American civilization and its development.”

Spurred on by Katherine Kellock, who was convinced that the United States needed its own series of travel guides, this desire grew into a federally funded project – the Federal Writers’ Project, part of the then-new Works Progress Administration’s Federal Number One. The Writers’ Project, in particular, was responsible for employing around 5,000 writers, researchers, and other white-collar jobs nationwide. But the Guides, in keeping with Alsberg’s original vision, were a love letter not to an idealized version of the country, but to the working man’s America.

It can be easy to dismiss this love as outdated nationalism, but the project itself was principally concerned with trying to break from this idea. As Jerrold Hirsch argues, the Writers’ Project was not interested in reinvigorating old nationalist love, but in “trying to redefine it […], to broaden the definition of who and what was American.” That’s why the New York City, Illinois, and Louisiana divisions, for example, employed a large number of black people in order to accurately write folklores and histories of said states, and one of the largest triumphs of the Federal Writers’ Project is the comprehensive oral history Slave Narratives collection.

So how do you juggle a travel guide and essays and a rediscovery of American identity? You focus on everyday life. Written in accessible English, with the type of flair that seems like it belongs in a novel rather than a travel guide, the WPA Guide to New York City describes Manhattan, for example, not through a bullet point list of facts, but punctuates its explanation of the area with paragraphs like:

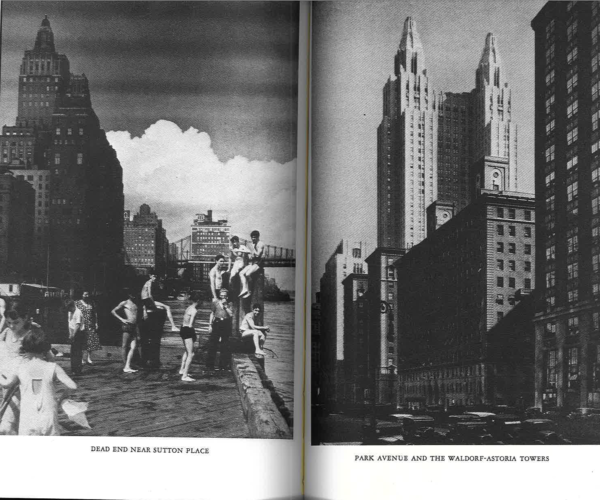

Instead of functioning as a very straightforward tour guide, then, the Guides attempt to tell the stories of the places they describe. One of the photos, for example, captures a group of boys playing near the river at Sutton Pier – while the next one shows off the architecture of the Waldorf Astoria. The New York City Guide specifically contains 89 photographs and 81 prints made by WPA employed artists and photographers, together with 38 maps of different parts of New York City.

As such, the Guides don’t shy away from the more tourist-y aspect either: they are, after all, travel guides. The WPA Guide to New York City starts with a general overview of the city before diving into its different neighborhoods. Information about which hotels or restaurants to visit is, of course, outdated at this point, but points of interests like Luna Park in Coney Island or the Metropolitan Museum of Art still reflect real attractions or cultural highlights.

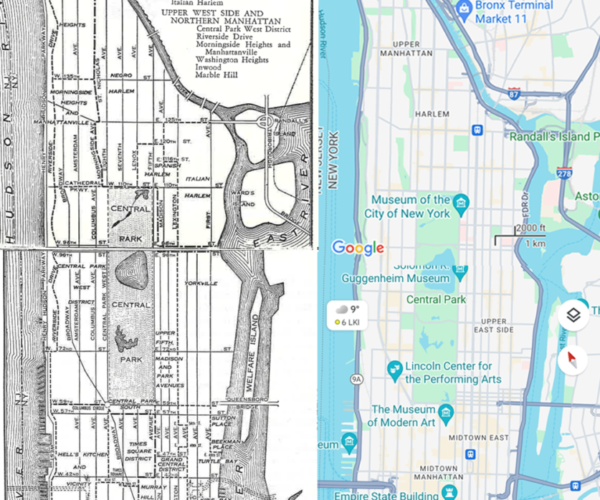

Different districts are each described with care – their namesakes, their colonial histories, who lives there and why – in a way a more general tour of the city might not always highlight. Harlem, for example, might not be divided among different ethnicities these days, but the Harlem Renaissance is a must-know period for anyone who comes to visit, and the Apollo Theater might not be as well-known to contemporary tourists as it should be.

The in-depth history of each borough, the photos, the prints, the listings of restaurants and different cuisines: the Guides present a (federally funded) way to travel back to the 1930s and discover an era of history that’s often described as dark and gloomy.

Plus, if you find yourself getting lost in Manhattan, the guide offers a handy key (and map!) to help you familiarize yourself with its many neighborhoods and grid-like streets.

All in all, the Guides still offer an interesting way to tour places you might already be familiar with. Apart from functioning as a time capsule, the Guides offer an encyclopedic yet realistic look into the United States of the past. They’re rife with the possibility for analysis – how did un(der)employed writers and surveyors envision the USA they were living in – but still retain their recreational function, maybe helping you find unexpected spots along the way. And as a federally funded relief effort for writers, researchers, and other white-collar workers – in the 1930s! – the Guides reflect a wider cultural lens than expected.

If you’re interested in reading more about the WPA Guides, the people behind them, or why the project switched hands, funding, and purpose because it was deemed “Un-American,” check out some of the RIAS collections on the subject! Apart from the Guides to New York City, Kansas, California, Illinois, and more, the RIAS has microfilm reels containing the full archives of the Federal Writers’ Project, the Works Progress/Projects Administration, and the FBI File on the House Committee on Un-American Activities.

This article was written using the following archival and digital sources available at the RIAS:

- The RIAS digital newspapers collection

- The WPA Guide to New York City: The Federal Writers’ Project Guide to 1930s New York / with an introduction by William H. Whyte (New York: New Press, 1992)

- Penkower, Monty Noam. The Federal Writers’ Project: A Study in Government Patronage of the Arts (Urbana-Champaign: U of Illinois P, 1977)

- Hirsch, Jerrold. Portrait of America: A Cultural History of the Federal Writers’ Project (Chapel Hill: U of North Carolina P, 2003)

Related archival collections include: