Today, if any of the approximately 3.1 million Dutch Americans wish to know what is going on in their ancestral land across the pond, they most likely are able to find out in a matter of seconds using this fabulous thing called the Internet. For those who went to the United States as part of the post-1845 Dutch emigration wave, this kind of luxury, needless to say, was completely absent. However, one of these migrants – a man from the hamlet of Zonnemaire, Zeeland, by the name of Jacob Quintus – founded the Sheboygan Nieuwsbode, setting the standard for the Dutch-language press in America.

The Dutch emigration wave to the United States that lasted from 1847 to 1857 “brought religious Seceders from the Hervormde Kerk (Reformed Church) by the thousands. Persecuted for their faith and penurious from the failure of the potato and rye crops, they sought a brighter future in a nation with religious liberty and cheap land.” Many workers from Zeeland-Flanders (Zeeuws-Vlaanderen), where Jacob Quintus had quite a number of acquaintances, voyaged to the western part of New York State. And when a group of 457 of these “Afgescheidenen” (Seceders) from Zeeland journeyed to the “New World,” this left a deep impression on the entire province. It was in this context that Quintus became enthralled with the idea of emigrating himself, and so he did.

On 27 september 1847, after a five-week journey aboard the sailing ship the Robert Parker, Quintus arrived in the port of New York. Seeking to profit from his language abilities, he published a Dutch-English dictionary and “tried to make a living as a teacher of French and German in Buffalo while awaiting the melting of the Great Lakes.” His desire for information gave him the idea to start selling the Zierikzeesche Nieuwsbode in America, and on 24 July 1848 this newspaper announced that J. Quintus was selling subscriptions in Buffalo (and in Albany in 1849) for a dollar and ten cents. When this turned out to be commercially successful, he “announced plans to start a newspaper in the Dutch language, De Hollandse Amerikaan.” His initial attempt in Buffalo failed; he found himself having to cope with bad experiences caused by other publishers. In particular, speculators in New York had circulated eight editions of the periodical De Nederlander in Noord-Amerika, but they ultimately did not keep up with it, meaning subscribers lost their money.

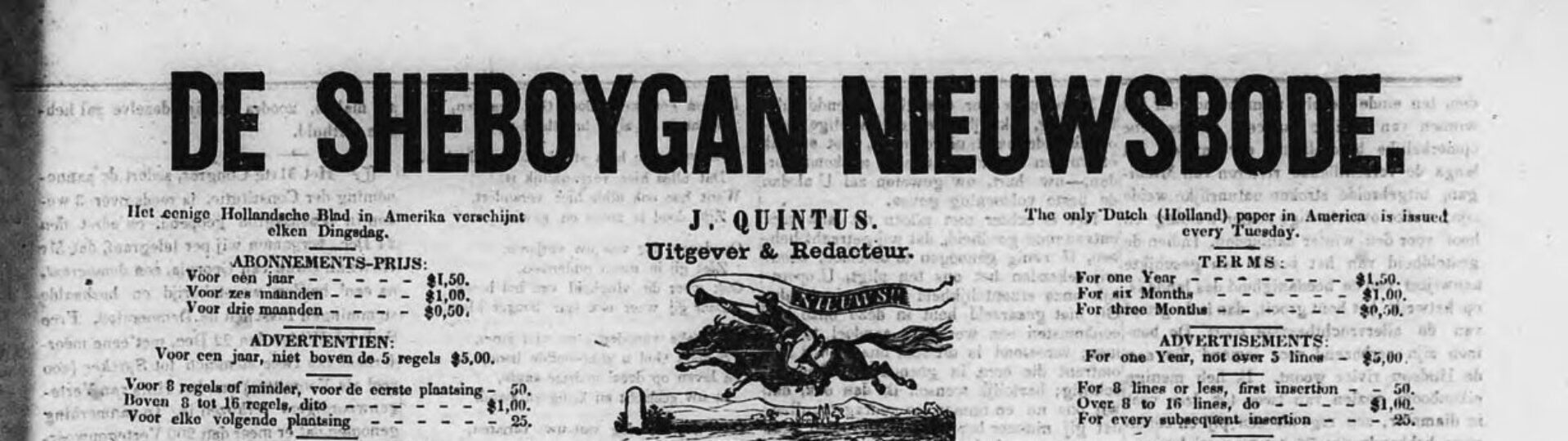

After “decid[ing] to settle in Sheboygan, Wisconsin, a small town with strong Dutch and German immigrant populations, close to Milwaukee on Lake Michigan.” he gave it another try—this time successfully. Directly adopting the format of the Zierikzeesche Nieuwsbode, he published the first edition of the Sheboygan Nieuwsbode on 16 October 1849. On its front page, the editors explain to the reader, “we have been ever occupied with the thought of publishing a newspaper in our own mother tongue, and time and again have we felt the necessity to do all in our ability not to stand too far behind other peoples from Europe, such as the French, the High Germans, the Danish, the Norwegian, and the Italians, who, if we are properly informed, all have newspapers in the native tongue” (translation). The Sheboygan Nieuwsbode “was intended to serve the Dutch reading immigrants … [and] Quintus soon became a most readable chronicler of social and political events in the new settlements.”

Not only did he publish a Dutch-language newspaper, Quintus also “quickly succeeded in convincing the powers in the Wisconsin legislature to do for the Dutch, what they had already been doing for the Germans immigrant population: to pay for the translation and printing of political reports.” Indeed, the Sheboygan Nieuwsbode of 24 January 1851 contained the governor’s annual message, which opened with the following line: “De jaarlijksche zamenkomst der Constitutionele Vertegenwoordigers eens verlichten volks, is voor de vertegenwoordigden eene gebeurtenis van niet gewoonlijk gewigt” (The annual assembly of an enlightened people’s Constitutional Representatives, is an event of unusual gravity for those who are represented). Demonstrating a marked level of political engagement, Quintus served as an intermediary for his fellow Dutch emigrants.

In addition to these more political and business-related functions, the Sheboygan Nieuwsbode, and later Dutch-American newspapers like it, featured poetry and prose. To give a brief illustration, the first few lines of one such poem, published in the Sheboygan Nieuwsbode of 29 January 1850, read:

Hoe gaarne toovert Gij, mijn dierbre fantazij,

Mij in den tijd terug van Neerlands hovaardij,

Toen ’t keine plekjen gronds, waarop ik ben geboren,

Geluk en roem en eer en grootheid was beschoren;

(How gladly does Thee, my dear fantasy / Conjure me back to the time of Dutch pride / When the small plot of land, on which I was born / Was endowed with happiness and fame and honor and greatness)

It is these kinds of poems that give an intriguing insight into the affective appeal that the old homeland continued to exercise on the Dutch immigrant communities. In fact, this particular poem could be seen as an outright glorification of Dutch colonial history. A few lines further down, it reads;

Hoe gaarn denk ik aan U, nooit te vergeten tijd,

Toen Neerlands driekleurvaan geeerd werd wijd en zijd,

Toen in elk wereldrond, tot aan de verste stranden,

De lof en roem weerklonk van onze Nederlanden;

Toen onze republiek den ocean gebood,

En leeuwen van de zee bemanden onze vloot!

(“How gladly do I think of you, time to never forget / When the Dutch tricolored banner was honored far and wide / When in every hemisphere, up to the farthest beaches / The praise and fame of our Netherlands resonated / When our republic commanded the ocean / And lions of the sea manned our fleet!”)

When examining the 1850s wave of Dutch emigration to the United States through a transnational lens, this kind of poetry nicely complements the news articles and numerous advertisements for local businesses that the rest of the Sheboygan Nieuwsbode was filled with. By presenting a more artistic rather than business-related perspective, these poems reflect some of the ways in which Dutch ethnic and cultural identity was perceived and maintained among the emigré community in the mid-19th century.

Although the rise of digital communication technologies would eventually render the (paper) format of Dutch-American newspapers obsolete, the story of Jacob Quintus and his Sheboygan Nieuwsbode gives a fascinating insight into how Dutch-American transnational connections were preserved and strengthened more than a century and a half ago.

This article was written using the Dutch-American Immigrants Newspapers collection at the RIAS. In addition to this archival material, the following secondary sources (also from the RIAS collection) were consulted:

- Bult, Conrad. “Dutch-American Newspapers: Their History and Role.” In The Dutch in America: Immigration, Settlement, and Cultural Change, edited by Robert P. Swieringa, 273–93. Rutgers University Press, 1985.

- Edelman, Hendrik. The Dutch Language Press in America: Two Centuries of Printing, Publishing and Bookselling. Nieuwkoop: De Graaf Publishers, 1986.

- Krabbendam, Hans. “Jacob Quintus (1821-1906) en de Sheboygan Nieuwsbode: Een Zeeuws model voor de Nederlandstalige pers in Amerika.” Tijdschrift Zeeland 18, no. 3 (September 2009): 103–111. Accessed via https://www.dezb.nl/dam/bestanden/Quintus.pdf.

- Swieringa, Robert P. “The New Immigration.” In Four Centuries of Dutch-American Relations 1906-2009, edited by Hans Krabbendam, Cornelis A. van Minnen, and Giles Scott-Smith, 295–306. Amsterdam: Uitgeverij Boom, 2009.