The Credibility Gap: Watergate and the Erosion of Trust

In the early hours of June 17, 1972, police arrested five men inside the Democratic National Committee headquarters at the Watergate complex in Washington, D.C. They wore business suits and surgical gloves. They carried lock picks, cameras, and electronic surveillance equipment. In the weeks that followed, investigators traced the money in their pockets back to the Committee for the Re-Election of the President. Fearing a competitive race, Nixon had sanctioned a broader campaign of sabotage against his opponents – and when the burglary was discovered, he worked to suppress the investigation. Within two years, a presidency was destroyed. Within a decade, so was something harder to measure: the trust people had in the American government.

Before the 1960s, trust in the federal government was relatively high. Approximately 75% of American citizens trusted the government to make good choices. By 1974, after years marked by the Vietnam War, unrest at home, and the Watergate scandal, trust had fallen to about a shocking 36%. The decline began in the 1960s, but some historians point to Watergate as the turning point after which the decline appeared irreversible. Time Magazine later called it “America’s most traumatic political experience of the century.”[1]

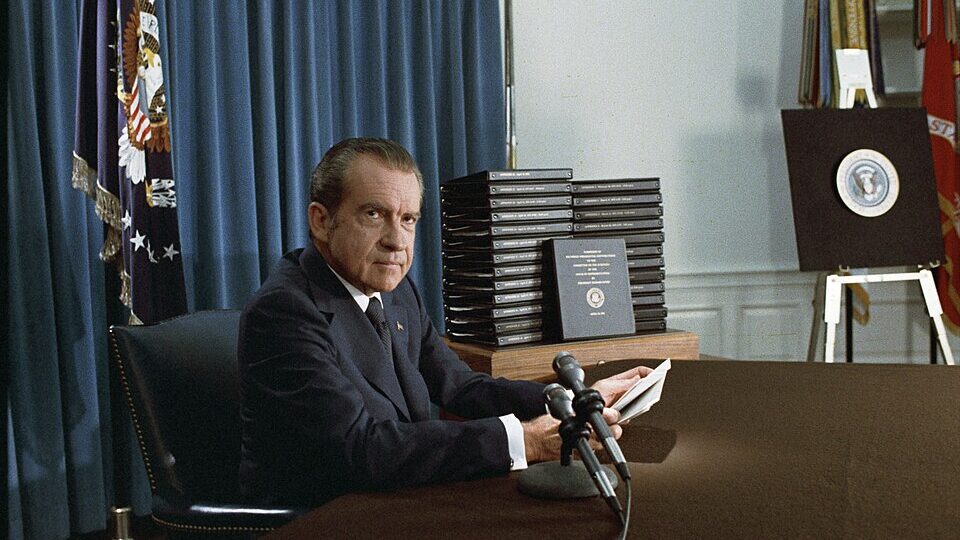

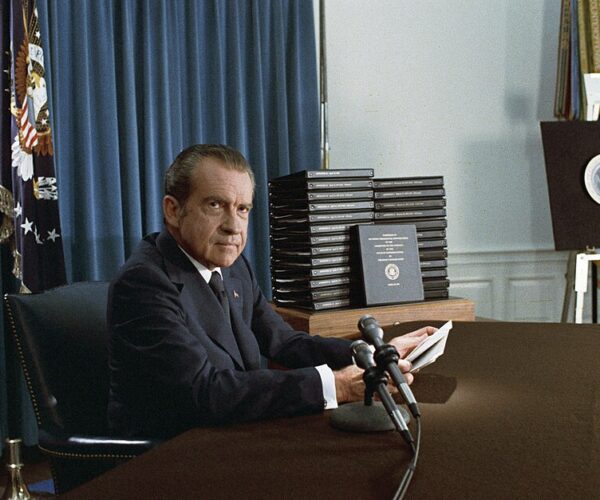

On 15 August 1973, President Nixon issued a statement denying any involvement. “I had no prior knowledge of the Watergate operation, and I neither knew of nor took part in any subsequent efforts to cover it up,” he declared. He emphasized that no witness had testified to his knowledge of the break-in, and he characterized some of the accusations against the White House and the Committee for the Re-election of the President as false, arguing that they were being amplified by intensive media coverage. “Not only was I unaware of any cover-up,” he insisted, “but at that time, and until March 21st, I was unaware that there was anything to cover up.” Nixon also refused to release the White House tapes, arguing that doing so would violate executive privilege and set a dangerous precedent – future advisors and diplomats would never speak candidly if they feared their conversations might be made public. He closed by reassuring the American people: “…I will continue to discharge to the best of my ability my Constitutional responsibilities as President of the United States.”

As Nixon denied involvement, the White House was quietly tracking public opinion. A White House memo from May 1973, summarizing internal polling, noted that only 5.4% of Americans ranked Watergate as the country’s top problem, and that in a hypothetical re-run of the 1972 election, Nixon would still defeat McGovern by a wide margin. Even if public support for Nixon initially held, cracks were already visible: 15.4% of respondents said Watergate had affected their lives, and of those, more than a third said it had shaken their trust in the president. These were early signs of a shift that would accelerate dramatically over the following year, as evidence emerged that Nixon had known far more than he admitted.

Just months earlier, the White House had projected an image of stability and competence. Internal campaign memos from August 1972 praised Nixon as a leader who had delivered “responsible, timely, moderately progressive, absorbable change,” while portraying McGovern as reckless and economically dangerous. Yet within a year, that carefully constructed image was unraveling. The gap between his public assurances and the emerging facts deepened the sense that the president could not be trusted.

Eventually, facing certain impeachment, Nixon resigned in August 1974 – the first president ever to do so. The damage to public trust was profound and lasting. According to Pew, the percentage of Americans trusting the government to do the right thing dropped from 54% in the early 1970s to the mid-30s after Nixon’s resignation, and never returned to pre-Watergate levels. For the next five decades, trust fluctuated between 20% and 40%, with one brief spike to around 60% after 9/11, but never recovering the confidence of the early 1960s.

The patterns that Watergate exposed – executive secrecy, manipulation of public opinion, contempt for legal constraints – did not end with Nixon’s departure. Iran-Contra revealed a White House running covert operations and lying to Congress. The Iraq War showed an administration shaping intelligence to justify a predetermined conclusion. Warrantless surveillance programs demonstrated how easily constitutional limits could be sidestepped in the name of security. Each episode reinforced what Watergate first taught Americans: that their government might be lying to them. Today, with trust in government near historic lows, that lesson has hardened into a default assumption. The 75% trust of the early 1960s is not just a number from another era – it marks a relationship between citizens and government that has yet to be rebuilt.

Sources:

Digital Resources at RIAS:

- Colson, Charles. Memo on Sindlinger Public Opinion Poll and Watergate Accusations. [United States: White House, May 7, 1973]. 7 pages. GALE Document Number: CK2349523050. Declassified September 25, 2002.

- McLaughlin, John. Memo on Nixon’s Strengths and Attacks on George McGovern. [United States: White House, August 8, 1972]. 4 pages. GALE Document Number: CK2349674947. Declassified December 15, 2004.

- Nixon, Richard M. Statement by the President on the Watergate Affair. [United States: White House, August 15, 1973]. 5 pages. GALE Document Number: CK2349680622. Declassified June 28, 2007.

- Price, Raymond, Jr. Memo on Republican Campaign Issues and Critique of George McGovern. [United States: White House, August 8, 1972]. 4 pages. GALE Document Number: CK2349719536. Declassified December 15, 2004.

Additional Sources Consulted:

- Pew Research Center. “Public Trust in Government: 1958–2024.” Feature, June 24, 2024. https://www.pewresearch.org/politics/2024/06/24/public-trust-in-government-1958-2024/

Secondary Sources:

- Emery, Fred. Watergate: The Corruption of American Politics and the Fall of Richard Nixon. New York: Times Books, 1994.

- Genovese, Michael A., and Iwan W. Morgan, eds. Watergate Remembered: The Legacy for American Politics. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2012.

- Olson, Keith W. Watergate: The Presidential Scandal That Shook America. Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 2016.

Images:

- National Archives & Records,

File:Nixon edited transcripts.jpg – Wikimedia Commons

- Oliver F. Atkins,

File:Nixon 30-0316a.jpg – Wikimedia Commons

[1] Michael A. Genovese and Iwan W. Morgan, eds., Watergate Remembered: The Legacy for American Politics (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2012), 1.