The League of Revolutionary Black Workers (LRBW)

On May 2, 1968, in response to a work speedup at a Chrysler automobile Plant (former Dodge Main plant) in Hamtramck, Detroit (Michigan) a Black worker, General Gordon Baker, Jr., led 4000 black and white workers out of the plant in a wildcat strike. After many years of struggle and resistance, that was the start of Detroit’s black workers struggle momentum that turned it into “the most important revolutionary action in the country” that would seek to change not only the automobile industry but the practices of American trade unionism.

Three days later, Chrysler fired Baker for violating the no-strike clause of the collective bargaining agreement between Chrysler and the United Auto Workers (UAW), the acknowledged worker’s union at the plant. As a result of the strike, Baker and other workers formed the Dodge Revolutionary Union Movement (DRUM). From 1968 into the early 1970s, DRUM worked to gain more power for African American industrial workers and to stop speed-ups, improve working conditions and salaries, and to change racist and discriminatory practices at Dodge Main and other plants in Michigan, the heart of the auto-industry.

Following DRUM’s lead, workers in several other automobile plants not only in Detroit but in Michigan formed revolutionary union movements (RUMs) like the Eldon Avenue Revolutionary Union Movement (ELRUM) at Chrysler’s Eldon Avenue Gear and Axle plant in November 1968, followed by new RUMs at other Chrysler, Ford, Dodge Truck, and Cadillac plants. In June 1969, all these organizations joined together in the LRBW.

Over the next two years, the LRBW and its affiliated organizations articulated a Marxist philosophy, conducted demonstrations against the automobile corporations and the UAW, published several newsletters, and organized social and cultural activities in support of the goal of winning power for African American workers.

In the summer of 1971, the LRBW split as a result of ideological differences. One faction, favored broadening the struggle beyond Detroit, eventually creating a black revolutionary political party that could present candidates at local elections. In June 1971, this group officially resigned from the LRBW and joined the Black Workers Congress, headed by James Forman, former executive secretary of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC). General Baker and others, however, argued that the LRBW needed to continue to focus on organizing black industrial workers in Detroit at the grassroots level.

The LRBW ended up being a significant and influential Black Power groups to emerge during the 1960s. Its approach and membership had a tremendous influence on black radicalism, the Left, and the radical wing of the labor movement, and was pivotal to analyze the intersection of racism, race and class in the “post-civil rights” era.

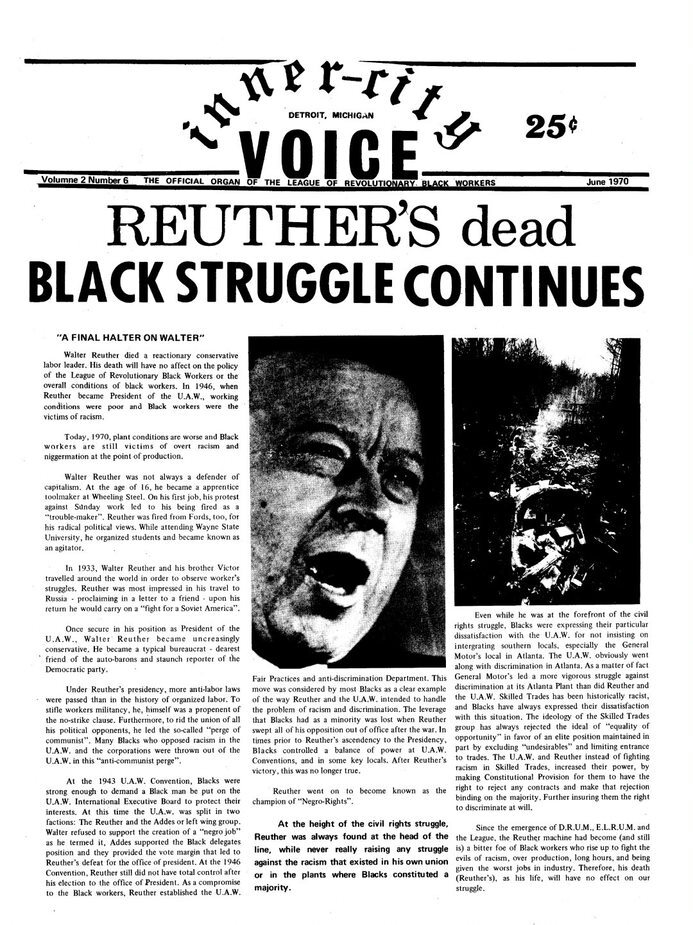

The Roosevelt Institute for American Studies sources clearly show that the LRBW was pivotal not only for the Civil Rights and Black Power Movement, but for the Black Labor movement of the 1970s. Through personal letters and correspondence, policy statements and program, LRBW and its affiliated organizations publications, their newsletters Inner City Voice and The South End, Detroit Police, IRS and FBI files and other miscellaneous materials and documents, the collection the RIAS have offers significant primary sources collected by one of the founding and most memorable members of the Dodge Revolutionary Union Movement (DRUM) and the LRBW, General Gordon Baker Jr., you can inquire on the rise and fall of the LRBW and its constituent organizations, as well as put in historical perspective the most important milestones and achievements of the struggle lead by the organization and its legacy.

A document that stands out in the collection is History and Derivation of the League of Revolutionary Black Workers (The Black Power Movement, part 4: League of Revolutionary Black Workers, Reel 1/3), that compiles the most important aspects related to the origin, ideology, theory and praxis of the organization, according to the perspective of the League itself.

This piece was also written using:

Robert Dudnick,“Black Storm rages in Auto Plant”, Guardian, March 8, 1969, in U.S. Congressional Record. Proceedings and Debates of the 91st Congress, 1st session, Vol. 115, Part 5, Washington DC: United States Government Printing Office, 1969, p. 6539.

The Black Power Movement, part 4: League of Revolutionary Black Workers, Reel 1/3.

The Black Power Movement, part 4: League of Revolutionary Black Workers, Reel 3/3 / Series 9: Oversize Materials