“Selling” the Marshall Plan to the Dutch: The ECA Mission to the Netherlands

On June 5, 1947, the U.S. Secretary of State, George C. Marshall, presented a plan to give economic aid to post-War Europe. Through the European Recovery Plan (ERP), or “Marshall Plan” as it came to be known, the United States aimed to revive the war-struck European economies, believing that economic instability could lead to political instability and in turn give way to the spread of Communism in the Old Continent. It was also economically beneficial to the United States, as it sustained the export of U.S. goods to Europe. Russia and Eastern Europe rejected the plan because of American-imposed financial and economic controls, as well as due to its goal to integrate Europe’s economies into a single market. The final plan was therefore implemented only in Western Europe.

Under the Marshall Plan, recipient countries paid for goods from the dollar area in national currencies with which they paid of their national debts, while the exporter was paid in dollars by its own country. Interestingly enough, 5 percent, —approximately 200 million dollar per year—of the sale of U.S. products through the ERP went to public diplomacy efforts to sell that same plan.

The way in which the Dutch government implemented the ERP is a good example of how important such a public diplomacy effort was. In fact, the bilateral agreement signed by the Netherlands and the United States on July 2, 1948, which laid down the conditions for U.S. aid to the Netherlands, explicitly stated that the Dutch government had to give a large amount of publicity to the Marshall Plan. A 1949 article in the Washington Post names the Netherlands as a “case in point” for how European governments were not only managing but also widely and publicly promoting the Marshall Plan aid in their countries.

The RIAS’ Dutch-American Diplomatic Relations microfilm collection contains a special collection of Marshall Plan Documents which is a perfect source to assess the success and development of this public diplomacy endeavor. This collection holds the documents from agencies different than the State Department, and it helps cast a new light not only on the policies of the Marshall Plan but on its actual execution on the ground. For instance, the collection concerning the Marshall Plan in the Netherlands contains the records of the Mission to the Netherlands under the Economic Cooperation Administration (ECA). The ECA was a temporary American agency established to implement the Marshall Plan. Its primary tasks were the distribution of financial aid across recipient countries and monitoring how the ERP-funds were spent.

The ECA Information Division in Washington, D.C., set the strategic goals for the Marshall Plan programs. These goals were coordinated with individual country missions by the Information Division of the Office of the Special Representative (OSR) in Paris. The ECA Mission to the Netherlands had its own information department, the “Information Office.” It set up publicity campaigns and had ample financial resources. The RIAS’ records of the Mission to the Netherlands under the ECA include many documents on the implementation of the information campaigns in the Netherlands. In the Netherlands, the Mission worked together with the Dutch Ministry of Economic Affairs, the Office of the Special Commissioner for the ERP under the Ministry of Foreign Affairs as well as the Ministry of Agriculture.

In a letter to Roscoe Drummond, chief of the Information Division of the OSR, Eugene Rachliss, who was the Publicity Officer of the ECA Mission to the Netherlands, describes “the Dutch situation” and points to those factors that should be kept in mind in planning and reviewing the information program in the Netherlands. He writes that “In general, the Dutch are pro-American, well-informed about, and in favor of, the Marshall Plan” and that the Netherlands is a highly literate country that is small and has good nationwide communication. He also finds it beneficial to their cause that the Dutch are likely to be part of a club or society and the government is moderately strong and in general sympathetic to the program’s cause. He also recognizes some “sensitive spots” that can hinder the effect of the Marshall Plan, first of which that the “pride” of the Netherlands is to be taken into consideration, for it was economically well off during the interbellum period, and now faces more “stubborn” economic problems than its Belgian neighbors. Because of this pride, “demonstrations of gratitude” from the Dutch are not to be pushed A survey of public opinion on the ERP also recognizes as the most challenging issue to convince the Dutch of the honest intentions of the Americans.

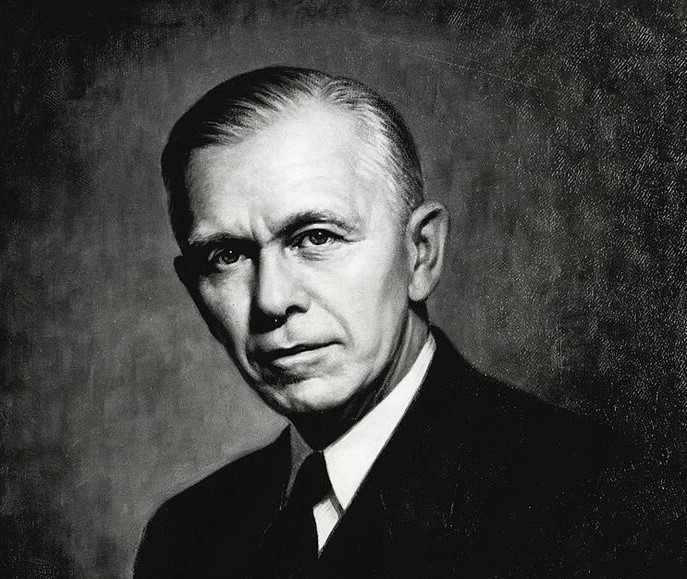

Clarence E. Hunter, Chief of the Special ECA Mission to the Netherlands, seems to bear this Dutch sensitive spot in mind in his speech broadcasted on Dutch radio station KRO (Katholieke Radio Omroep or “Catholic Radio Broadcasting”). He states that, while the Netherlands is a “small country in area” it ranks fifth among recipient countries in the amount of aid received, and the Dutch are receiving the largest sum per capita. In his speech, he chooses not to focus on the Dutch problems, but on the problems that Americans face. Hunter emphasizes that while the “average American” is “generous”, he is also interested in peace and economic security at home. For this reason, Hunter stresses that prosperity in the Netherlands and the rest of Europe is beneficial for the American economic well-being as well. Moreover, Hunter draws a parallel between the average American and their Dutch counterparts by asking the Dutch citizens to think of Americans, whose tax revenue is used to fund the ERP, as “steel-puddlers, shop-girls, clerks, musicians, lumber-men, coy-boys, printers, fishermen, executives, street-car conductors, bankers, butchers, movie actors, scientists, farmers, teachers and so on.”

Besides fostering a common understanding between the two cultures, Marshall Plan promotional officers in the Netherlands were busy setting up an information campaign that could efficiently deal with the “pillarization” of Dutch society, that is a strict separation into groups with different religious and political ideas each one with its own newspaper, radio station, labor union, farm organization, and school. This meant that in the Information Division’s dealings with the Dutch press, certain political and religious factors had to be taken into account. Because of this separation, “flamboyant methods” of advertising or the promotion of certain ideas was difficult, and there were “few individuals or groups experienced in the use of American methods to sell or promote a program”.

Among these methods, the visual ones seemed to be the ones that were working better. Rachliss found that the Dutch were especially receptive to posters and exhibitions, calling it “the most dramatic, effective way” of promoting the Marshall Plan to the Dutch. Many pamphlets were produced to sell the Marshall Plan, and distributed through reprints in Dutch newspapers, as well as in schools, labor union offices and the recreation and lunch rooms of major factories. Pamphlets were even put in plane seats of KLM flights. Moreover, a “Marshall Day” fair as well as photo and poster contests were organized to promote the ERP.

In the fall of 1950, two years after the implementation of the ERP, when integration of Europe had become the main goal of the ERP, the Intra-European Cooperation for a Better Standard of Living Poster Contest was held. The winning work, “All Our Colours to the Mast,” promoted this idea through its depiction of a ship with sails made of flags from each country and was distributed all over the world.

With the coming of the Korean War in June 1950, a crucial moment in the Cold War, came not only a larger emphasis on “hard power” in the form of military aid and the establishment of the American national security state, but also on strengthening American “soft power” in the form of psychological warfare and propaganda. This becomes evident in documents on the ECA’s information policy. In a paper outlining its new information policy in September 1950, sent to Western European Information Officers by head of the Information Office Roscoe Drummond, the policy is described as opposing “the Big Lie [of Communist propaganda]” with “the Big Truth”. Moreover, rather than avoiding the word “propaganda,” the document describes the American information policy as “our major propaganda effort,” “democratic propaganda” and “American propaganda”.

The two main themes that the new information policy proposal sets forth are “peace” and “progress”, which in turn are supported by sub-themes from pro-democratic and anti-Communist approaches. The anti-Communist part of the campaign was to be “an aggressive campaign designed to tear the mask of peace from the war-like plans and actions of the Soviet Union” which tone is “the cold voice of ruthless exposure”.

In the course of the years the ERP increasingly became a political instrument in the U.S. Cold War strategy. From 1951 onwards, the increase of military spending became a condition for aid. As phrased in a document outlining what this meant for ECA information policy, the “recovery phase” had ended and the “defense phase” begun. Under the Mutual Defense Assistance Program, the U.S. went to also give military aid to European countries, among which the Netherlands. The ECA recognized that its “evolution into a principal implement for free world rearmament” demanded a “fresh direction” in their informational policies and operations. While it was important for the ECA to “retain [their] own clear identity and freedom of action,” closer cooperation with the Department of State and Defense had now become necessary. In October 1951, the economic and military aid programs were dissolved into the Mutual Security Act. The ECA then became the Mutual Security Agency.

This article was written using the following microfilm archive:

– Record Group 469 Records of the Agency for International Development and Predecessor Agencies. Mission to the Netherlands, 1949-1953 (7 reels) 27.

And the following books:

– Nederland en het Marshall-plan : een bronnenoverzicht en filmografie, 1947-1953, Ralph Dingemans, Rian Romme. – Den Haag : Algemeen Rijksarchief, 1997.

– Images of the Marshall Plan in Europe : films, photographs, exhibits, posters Günter Bischof, Dieter Stiefel (eds.) Innsbruck : Studienverlag, 2009.